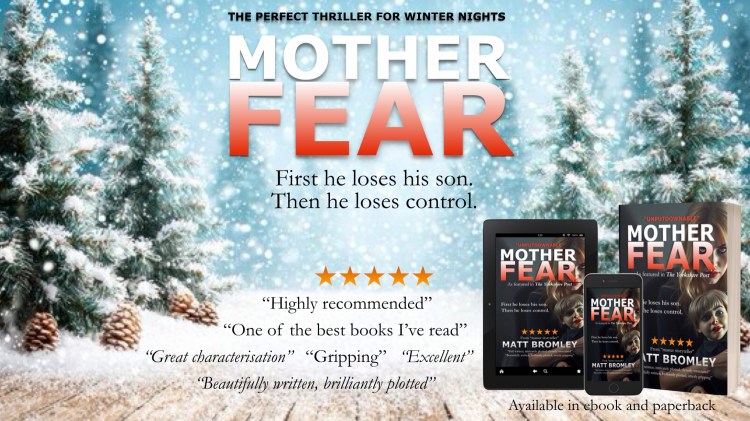

Mother Fear: Free Sample

Paperback | Kindle | Apple Books

The following text is copyright © Matt Bromley 2025. Do not reproduce without permission.

Chapter One

29 July 2025

If this were an airport novel, a blockbusting beach-read like the tome sat unread on Kate’s sun-lounger, then the juxtaposition of place and prose would have been less jarring. When Tom picked Oliver’s phone up, there would have been a clap of thunder or flash of lightning. But, as it was, the Spanish skies refused to play pathetic fallacy; instead, they remained stubbornly sun streaked.

There were no shrieks of terror, either; only the playful cries of excited children plummeting down spiralled waterslides shaped like pirate ships and splashing into the pool.

And yet the impact was no less tragic. From the moment he’d heard the message notification on his son’s phone – hastily abandoned at the foot of his sun-lounger when Oliver decided to divebomb the pool – Tom had felt bile rising from his stomach.

If he could wind back those minutes and leave the phone untouched, the messages unread, there to be discovered by their intended recipient when he returned, laughing and exhilarated, to towel himself off and collapse onto his lounger, would Tom do so? Would he wish the knowledge unknown, the world un-tilted, reality unaltered?

It was impossible to say which side of those sliding doors offered the greatest chance of happiness. Or the least pain.

When the phone beeped, Tom looked first at the lit-up screen then at the pool where Oliver was occupied in horseplay with Adam. Tom sat up on his sun-lounger and reached for the phone. Angling the screen, he saw the notification: 1 new message from Mum.

Tom palmed the phone and entered the passcode – Oliver’s date of birth. He navigated to messages and paused, perched on the edge of an intrusive act. He weighed the moral dilemma in his mind: invading a person’s privacy versus safeguarding a son. He glanced furtively at the pool. Oliver was further away now, he and Adam queuing for the slides. Tom clicked on the speech bubble and scrolled down the message list. There was nothing else to raise any red flags, just a few texts from schoolfriends and an innocuous gif from Charlie. But there, at the top, was a new message from her.

It was three years since Tom and Maggie had separated and Tom had tried hard to rehabilitate himself, to balm the hurt; to rationalise, repair, restore. But he’d done little more than polish the pain into a thin veneer. And now, feeling her presence again, albeit electronically, scratched that superficial surface and exposed the unhealed scars and open wounds beneath.

Tom hesitated, balancing a different kind of conundrum now: to leave undiscovered what his ex-wife and son were discussing, and thus retain his ignorance so that he could enjoy the rest of his family’s holiday, or pick at that weeping sore, in the hope he’d be empowered by whatever knowledge he uncovered. A glimpse at the text’s first few words, previewed on the message list, was enough to force a decision. “He’s a fucking joke…”

Tom was in no doubt the ‘he’ in question was him. He opened the message and, as he read on, felt suddenly alien to his surroundings. He was there but elsewhere, present but absent. He scrolled back to try make sense of what he was reading, to place in a meaningful context this sickening exchange between mother and son. But the further he scrolled, reading the conversation in reverse, the more disconnected he became and the more he feared that his perception of the world was not his son’s reality. He felt nauseous, light-headed. His heart pounded. His breathing became heavy.

“Seen a ghost?”

Tom hurriedly hid the phone under his beach towel and looked up. Kate stood at the end of his sun-lounger haloed in the midday sun.

“You’re the only person who’s getting paler in this heat. What you got there?” She nodded to Tom’s beach towel where Oliver’s phone was forcing a bulge.

Tom slid the phone out and signalled for Kate to sit on the lounger next to him.

“You need to see this. And I need a drink.”

“What do you want me to see? Isn’t that Olly’s phone?”

Tom took a gulp of the cocktail that had warmed in the sun and felt the tepid, sickly sweet liquid travel down his body and sit heavily in his stomach.

“It’s her. The Psycho.”

Mother Fear continues after this short intermission…

*

20 January 2013

When Tom looked down at the newborn baby cradled in his arms, his doubts began to dissipate. For this – a memory in which he would seek succour in the years to come – was the moment he first allowed himself to believe that the child could be his.

He’d always wanted to believe he was the father, that he would have an heir, someone he could love – and who would love him – unconditionally. But wanting something to be true is not the same as feeling it, knowing it. And his doubts were long-held and deep-rooted. Two months after they’d begun dating, Maggie had told him – whilst they’d been celebrating his birthday – that she was pregnant. Tom had known that he could not have been the father because on the two occasions they’d slept together, they’d used contraception. He’d presumed that the father was Graham, Maggie’s previous boyfriend, with whom she’d had an unsatisfying, six-month relationship she’d ended by text soon after she and Tom had first slept together one drunken night out. But he’d been wrong. Upon interrogation, Maggie had revealed that the baby was in fact Jimmy’s, a man she’d had an affair with behind Graham’s back; an affair Tom had not been wholly convinced had ended.

The more questions he’d asked, the more tangled he’d become in Maggie’s complex past and the more concerned he’d become about her integrity. The more she’d told him, the less he thought he’d known, and the less he’d wanted to know.

But when he looked at his son for the first time and saw a child wearing a mask of its father’s face, he finally allowed himself to believe that he’d become a dad.

In an evolutionary sleight of hand designed to protect a firstborn from being cast out – or worse, eaten – by its father, nature lends it its father’s features.

Tom looked at his baby son, moments ago brought naked into the world, vulnerable and weak, saw himself reflected there, and something shifted inside him, a biological rewiring of every chip and circuit. Though not a violent man, he knew then that he would do anything to protect this baby. He knew then that his own survival instinct had been shuffled back in the pack. A new life had taken top trumps now.

He looked at the baby in his arms and the baby blinked back at him, and in a primal pact forged in blood and tears, he swore he’d do whatever necessary to protect this child.

Chapter Two

29 July 2025

“What the fuck?” Kate stared at the phone Tom had just passed her.

Tom’s pulse was still racing, he could feel blood drumming at his temples and pressure building behind his eyes.

“What do we do? Confront him?” Tom asked.

Kate thought for a moment. “If he knows we’ve seen the messages, he’ll change his passcode. We need to see what the Psycho plans to do next. And we need to survive this holiday.”

Tom knew Kate was right. All hell would break loose if he confronted Oliver about the messages now. How could they possibly play happy families after that?

The four of them, him and Kate, Oliver and Adam, were cocooned in a small poolside apartment for the next three days and then had a two-hour transfer to the airport and a long flight home to contend with. There was no other option but to unsee the messages, at least as far as Oliver and Adam were concerned. Get through the next few days and, once home, decide what to do.

“We need to monitor his phone, though,” Kate said. “And you should take screenshots. No, on second thoughts, take photos of the messages from your phone. He can’t suspect we know.”

Kate handed Tom the phone and he swiped right on the messages to mark them as unread.

“Is that my phone?”

Oliver had returned from the pool and now loomed over Tom, dripping chlorinated water onto his lounger. He swept his fringe back, splashing Tom in the process.

“Yeah, mate. It just pinged. Think it’s your mum.”

Tom handed the phone over and Oliver glanced at it then threw it onto his own sun-lounger. He picked up his beach towel and began drying himself off.

“Where’s Adam?” Kate asked. Tom knew she was trying hard to keep her voice calm and casual.

“Dunno,” Oliver replied with a shrug. “I’m not his keeper.”

With that, he dropped down onto his lounger, twisted AirPods into his ears, and retreated into a private world. Not yet in his teens yet every inch a teenager.

The day passed slowly and predictably. Tom read by the pool and, when he felt himself frying in the heat, took the occasional dip in the water. Kate largely stayed in the pool, swimming the odd length, and chatting to other parents by the water’s edge. She protested – somewhat unconvincingly to Tom’s mind – when the hotel reps pressured her into playing a game of water volleyball, but she played a competitive game nonetheless and celebrated with enthusiastic high-fives when her team won.

Adam spent most of the afternoon on the waterslides or sitting in the shade of the poolside bar with a soft drink or ice cream, playing games on his phone. He was quiet and uncommunicative, as if picking at the bones of an argument.

Oliver was in and out of the water. There were several more message notifications over the course of the afternoon and, with each one, Oliver appeared to become more furtive. Occasionally, a smirk – or was it a grimace? – crept across his face and he frantically thumbed out a response. When asked, he shrugged it off and said he was just chatting with some friends from school about football and music.

Mother Fear continues after this short intermission…

*

After half a day spent acclimatising to their new surroundings, the four of them had quickly fallen into a daily routine. They showered and dressed, taking quick turns in the shared bathroom, then circled each other by the mirror like ballroom dancers tentatively rehearsing a new routine. Then they headed down to the buffet restaurant for breakfast. Even this had become habitual: Kate poured coffee and orange juice, then Tom brought a selection of pastries to the table for the four of them to pick at. Oliver and Adam went to the hot buffet and returned with mountains of bacon, sausages, eggs, and hashbrowns; Tom and Kate queued at the omelette station, always opting for the same selection of toppings – ham, cheese, and mushrooms. When their plates were empty and their stomachs full, they went on the hunt for well-placed sun-loungers by the pool, and, struggling, cursed their compliance with the hotel rule about not reserving beds before breakfast.

The rest of the morning was occupied by the pool, soft drinks until eleven, then onto beers and cocktails. A late lunch was taken at the terrace bar, alternating between burgers and pizzas, always eaten at leisure to give their skin some time to recover from the sun.

After a few more hours by the pool, they had a valedictory cocktail before returning to their room to shower and get dressed for dinner.

Their evening meal was also a leisurely affair. Tom, determined to make the most of the all-inclusive, always had three courses, including an often-eclectic main of world cuisine. Feeling over-full and sometimes regretful of their gluttony, they took the short stroll from the restaurant to the open-air theatre where they ordered cocktails, fought off insect bites, and waited for the evening’s entertainment: a Russian Roulette of music, magic, and mirth.

Almost as repetitive and predictable as their daily routine was the tempestuous nature of Oliver and Adam’s relationship. At various points of the day, they were inseparable, huddled in conspiratorial conversations, or playing together in the pool, still young enough to enjoy a private and imaginary world of make-believe. But at other times, they were as distant and unfamiliar as strangers, sullen and prickly, each ready to snap at the slightest provocation.

Today was proving pricklier than most. After Oliver had returned from the pool to retrieve his phone, he’d remained for some time plugged into his music and thumbing out messages. Adam was briefly unaccounted for but was later spotted sitting in the shade of the poolside bar. Tom watched over the top of his sunglasses as Kate heaved herself out of the pool, water rippling in concentric circles around her, and walked over to her son.

There was a brief, muted exchange before Kate pulled up a seat alongside Adam and sat down. The staccato rhythm of Kate’s speech suggested she was asking questions; the pauses between implied Adam was in no mood to answer them. Instead, he sat impassively, shoulders sloped, eyes fixed on a patch of ground between his feet. After a few minutes, and upon receiving no reply, Kate stood up, placed a hand softly on the small of Adam’s back, and walked around the pool, weaving her way in and out of sun-loungers which had been moved to track the sun, and now stood like an army of toy soldiers circling an enemy.

“What was all that about?” Tom asked as Kate lowered herself onto the end of her sun-lounger.

“Your guess is as good as mine.”

Tom sat upright, squinting in the low afternoon sun.

“Is he okay?”

“Something’s happened,” Kate said as she shifted her gaze from Tom to Oliver and back again. “He won’t say what.”

Taking his cue, Tom waved a hand across Oliver’s eyeline. Oliver flicked his head to ask what Tom wanted. Tom mimed the removal of earphones and, somewhat reluctantly, Oliver obliged.

“Any idea what’s wrong with Adam, mate?” Tom asked as jovially as he could, careful to keep any hint of accusation out of his tone.

“Why, what’s he said?”

“Nothing. That’s the problem. He’s taken himself off over there, won’t talk to your mum –”

Tom’s voice faltered on the word ‘mum’, which until an hour ago would have caused no such consternation, but now felt like a grenade, pin-pulled and thrown into the conversation.

It had been Oliver’s suggestion to call Kate ‘mum’, unprompted and somewhat unexpected. Tom and Kate had sat him and Adam down to talk about how they were feeling about the changes in their lives. They’d had several conversations with the boys since their families had started to knit together, both believing that honesty and transparency were always the best policies.

They had kept their relationship secret for two months until they’d both felt confident it was serious. They’d told each other that their sons would always come first and that the boys had to be comfortable with any proposed changes in their lives.

Both boys, when they were told that their parents were dating, had claimed to have known all along; both said they were happy because their parents deserved to find someone to love and someone who loved them in return.

At first, Tom and Kate had asked their sons if they were happy to spend some weekends together, the four of them. Later, the boys were asked if they had any objections to the four of them moving in together. In fact, at every step of the way, careful consideration had been given to how Oliver and Adam would feel about any changes to their routines, as well as to what Tom and Kate would do if, at any point, either boy objected to those changes. But the objections never came.

Oliver and Adam had bonded immediately, begging their respective parents for a sleepover the first day they’d met. Adam had instantly bonded with Tom, too. Never having had a father figure before, Adam seemed to relish there being a man around the house, someone to take him to football practice and with whom to go cycling. Oliver adored Kate because she fussed over him, made sure he had whatever he needed, quietly picked up the clothes he’d abandoned on his bedroom floor before his dad saw them, and gave him extra helpings at mealtimes and secret snacks in his packed lunch.

The transition had not been perfect, of course. There had been the occasional argument between Oliver and Adam, usually a territorial dispute or the product of envy. Tom and Kate had bickered, too, from time to time, as they navigated a new life of compromise, bending to each other’s ways and wills, testing boundaries and discovering dividing lines.

But no one resented or resisted the reshaping of their family. And so, although they’d not anticipated it, and were somewhat unprepared for it, it had not come as a complete shock when Oliver had asked if he could start calling Kate ‘mum’.

“Are you sure that’s what you want?” Tom had replied, as he and Kate shared a look halfway between surprise and cautious delight.

“Yes. Definitely. Because she is – you are! My mum, I mean. You’re marrying my dad. You look after me, feed me, wash my clothes, nag me about not making my bed… You’re more of a mum to me than my actual mum. More of a mum than she’s ever been.”

Tom and Kate agreed to think it over and speak to Adam to see how he’d feel about it.

“Does that mean I can call you ‘dad’?” had been Adam’s excited response. And thus, it had been agreed.

“What about your mum, though?” Tom had asked when he and Kate sat Oliver down a week later to give their permission for the change.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, what will she say if she knows you’ve started calling Kate ‘mum’. I don’t think she’ll approve, do you?” Tom’s look assured Oliver that he knew this to be the understatement of the century.

“Does she have to know?” Oliver said nervously.

“That’s your call. I won’t tell her. She doesn’t talk to me anyway. I just want what’s best for you, Ols; don’t want you to get into any bother, that’s all.”

Within days, the sound of Oliver calling Kate ‘mum’ had become as natural as any other everyday utterance, as had Adam’s new moniker for Tom. Now, Tom thought, it would surely jar if Oliver reverted to calling Kate by her forename, as if she were a stranger to him. Certainly, Tom knew that he would not like it if Adam retreated like this. It would seem insulting somehow, like an intentional slur, an attempt to disrespect or belittle him. And it would undoubtedly create distance, break some bond, shatter some link in the chain they’d carefully soldered to bind them together.

*

Oliver thought for a moment, wrestling with a response. Eventually, he said: “Adam’s just, well, a bit too sensitive sometimes, that’s all. We were just messing about on the slides, pushing each other. Then he got annoyed and stormed off.”

Tom felt Kate’s eyes drilling into his back. There’s got to be more to it.

“Are you sure that’s all it is? No one hurt anyone else? Said anything unkind?” Tom prompted.

“He pushed me, I pushed him back. That’s it. Now, can I listen to my music please?”

Without awaiting a reply, Oliver pushed his AirPods back into his ears, laid down, and closed his eyes. But moments later, his hand felt for his phone and, finding it, he began tapping out a message.

Tom swung himself back onto his sun-lounger and looked at Kate who was flattening her beach towel and slipping on her sliders. They need not speak. They knew they were thinking the same thing. I bet he’s messaging the Psycho, telling her we’re picking on him, telling her he hates it here, hates us and can’t wait to go home to her.

But the question gnawing away inside Tom’s mind was the same question that had been bouncing off the walls of his skull like a rubber ball since he’d first read those messages between mother and son. Did Oliver really mean it? Had she finally got to him, worn him down, manipulated him into believing her lies? Or was he simply too scared to confront her with the truth?

Of course, there was another option, a middle ground on which Oliver could have sought refuge. After all, it was the no-man’s-land on which Tom himself had dug trenches often enough. Perhaps Oliver simply went along with his mum to please her, appease her; to keep on her good side and maintain the ceasefire. Tom knew all too well that life’s easier when Maggie is happy, when no one challenges her.

The problem for Tom was that none of those options gave him any comfort. Whatever was going on, he knew his son – this vulnerable boy who still, from time and time when he pulled certain facial expressions, looked like him, even if he was becoming less like him every day – was being failed by his parents and that he would carry the emotional scars with him for the rest of his life.

Tom had made a solemn promise to Oliver when he’d first held him in his arms twelve years ago. And he’d failed. Yes, he’d protected him from the outside world – from school bullies, bike accidents, and bee stings; and he’d given every part of himself to this child. But in the end, he’d been unable – or unwilling – to protect his son from the enemy within.