60 self-evaluation questions to help you audit your curriculum

In my 2016 book, Making KS3 Count, there’s a section called ‘Making Curriculum Count’ in which I advocate a more joined-up approach to curriculum design to ensure greater continuity across the various years, key stages and phases of education. I also advise that schools plan engaging curriculums that do more than merely prepare pupils for qualifications.

I wrote that book in 2015 and, when I began speaking on the subject at conferences and on training courses in 2016, audience responses convinced me there was much more to be said about the curriculum… curriculum thinking was almost non-existent. The school curriculum had become synonymous with the National Curriculum or, worse still, the timetable.

Accordingly, in 2017, I began planning what would become my 2019 book, School & College Curriculum Design. It would be a practical guide to designing an ambitious, broad and balanced, planned and sequenced, and truly inclusive curriculum.

I vividly remember that I was in the middle of writing School & College Curriculum Design (or SCCD as the cool kids call it) when Amanda Spielman replaced Sir Michael Wilshaw as the Chief Inspector of Schools, and one of Spielman’s first acts as head of Ofsted was to give a speech at the Festival of Education in which, coincidentally, she trumpeted the importance of the school curriculum.

Spielman argued that schools had lost sight of the real substance of education: “Not the exam grades or the progress scores, important though they are, but instead the real meat of what is taught in our schools and colleges: the curriculum.”

She went on to say that, although it’s true education should prepare young people to succeed in life and make their contribution in the labour market, “to reduce education […] to this kind of functionalist level is rather wretched.” Instead, education “should be about broadening minds, enriching communities and advancing civilisation [and ultimately] about leaving the world a better place than we found it.”

In short, Spielman said that many school practices reflected “a tendency to mistake badges and stickers for learning itself… [and put] the interests of schools ahead of the interests of the children in them.” She said we “should be ashamed [that we had] let such behaviour persist for so long.”

Of course, it was not difficult to see why such behaviour had persisted: the government’s accountability system, centred on performance tables, was undoubtedly at the heart of the matter, aided and abetted by Spielman’s own organisation, of course!

But the sorts of ‘system-gaming’ Spielman bemoaned were clearly not in pupils’ best interests. They put league table performance ahead of what was morally right for young people, and thus stood opposed to delivering a good education.

I had already formulated the 6-step process for tackling curriculum design that would sit at the heart of SCCD when Ofsted began consulting on a new Education Inspection Framework (EIF) to make flesh Spielman’s words.

My 6-step process posited that schools needed to be clearer about the purpose of education in their institutions and to have a well-defined idea of what success should look like at the end of learners’ journeys. It also embodied an approach to sequencing learning and to ensuring ambition for all whilst better understanding the causes and tackling the consequences of academic disadvantage.

At first, then, it felt fortuitous that Spielman’s draft EIF said schools should identify ambitious ‘end points’ and talked of using the curriculum to tackle social justice issues. But soon it felt like my thunder had been stolen and my book would be regarded as cashing in on school leaders’ desperation to bend to Ofsted’s will. As we were preparing for publication, news came of several competing titles that were in the pipeline and so I also wondered if my book would be crowded out by some louder voices from the sector.

I needn’t have worried. When SCCD came out in 2019, the response was fantastic. In fact, many schools adopted my 6-step model to redesign their curriculums. Many leaders cited the book as being instrumental in securing good inspection outcomes and, more importantly, to raising aspirations and narrowing attainment gaps. Reviewers described it as “compelling”, “inspiring”, and “invaluable”, and urged others “you NEED this book” because it was “not to be missed”. Admittedly, one reviewer described it as “fairly patronising”, but you can’t win ‘em all!

The second instalment – which focused on how curriculum plans can be translated into classroom practice in a way that leads to long-term learning – was published in 2020. And, in 2021, the final instalment – which explored ways of evaluating curriculum design and delivery and improving assessment practices – completed the trilogy.

I continued to speak on the subject at countless conferences and on numerous courses. And I continued to work with many schools and colleges on putting the books’ theories into practice. But one thing was repeatedly asked of me: are there any plans to publish all three books in one volume that can be more easily shared with colleagues? The answer has always been ‘no’. Until now, that is.

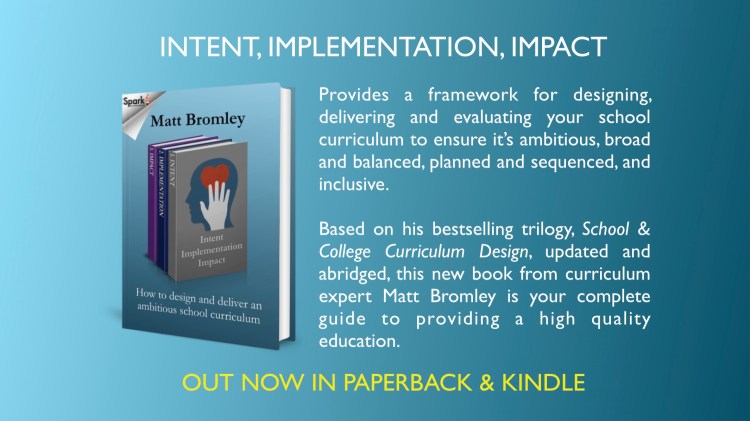

At the start of September, Intent Implementation Impact: How to Design and Deliver an Ambitious School Curriculum was published by Spark Education Books. It is not a simple ‘cut and paste’ job, either; it is much abridged, refined and updated. It’s sharper and easier to dip into when help is needed most. It is, dare I say, the complete guide to planning, teaching and assessing a high-quality education.

The blurb says it best:

“Intent is all the planning that happens before teaching happens. Implementation is how those plans are translated into classroom practice to facilitate long-term learning. Impact is how curriculum planning, teaching and learning, and learner progress and outcomes are measured – not least the extent to which learners are prepared for the next stage of their lives. Taken together, therefore, the ‘3Is’ provide a framework for designing, delivering and evaluating the school curriculum to ensure it is ambitious, broad and balanced, planned and sequenced, and inclusive. Based on his bestselling trilogy, School & College Curriculum Design, updated and abridged, this new book is your complete guide to providing a high quality education.”

You can find out more about the book at http://bit.ly/beBOOKS where you can also read free previews.

Meantime, to help you on your own curriculum journey, here are some self-evaluation questions taken from the book which you may wish to consider…

Intent

A good curriculum is a living organism, forever changing in response to reality. Curriculum design, therefore, should be a cyclical process. A curriculum should not be designed then left to stagnate. Rather, we should design a curriculum, teach it, assess it to see if it’s working as well as we had hoped, then redesign it in light of our findings. To help, ask:

Is our curriculum ambitious enough?

- Does our curriculum teach the knowledge and skills learners need to take advantage of the opportunities, responsibilities and experiences of later life?

- Does our curriculum reflect our school’s local context? Does it address typical gaps in learners’ knowledge and skills?

- Does our curriculum bring the local community into school and take learners out into the community?

- Does our curriculum respond to our learners’ particular life experiences?

- Is our curriculum sufficiently broad to ensure learners are taught as many different subject disciplines as possible for as long as possible?

- Is our curriculum sufficiently balanced so that each subject discipline has a fair amount of space on the timetable to deliver both breadth and depth?

- Are learners able to study a strong academic core of subjects but also afforded a well-rounded education including in the arts?

- Do we account for the hidden curriculum and ensure there are no inconsistencies or contradictions between what we explicitly teach in lessons and what we teach by way of the values, behaviours, and attitudes all our staff display daily, and by the quality of the learning environment and our rules and routines?

Have we identified the right destinations?

- Is it clear what ‘end points’ we are building towards as a school and in each subject discipline that we teach?

- Is it clear what our learners need to know and be able to do at each stage to reach those end points?

- Will these end points fully prepare learners for the next stage of their education, employment, and lives?

- Do we make explicit links between related end points within and across subject disciplines?

- As well as subject-specific knowledge and skills, do we also identify the research and study skills – and indeed other cross-curricular skills – that our learners need to succeed?

- Are skills explicitly taught and reinforced? Are they taught consistently across all subjects where applicable?

- Do we ensure that the end points of each part of our curriculum seamlessly join to the starting points of the next and so on, so that we achieve curriculum continuity and so that transitions between the various years, key stages and phases of education are as smooth as they can be?

Have we planned and sequenced our curriculum effectively?

- Does our planning ensure that new knowledge and skills build on what has been taught before and towards these clearly defined end points?

- Is there an appropriate pace that allows for sufficient breadth and depth?

- Is content taught in a logical progression, systematically and explicitly enough for all learners to acquire the intended knowledge and skills?

- Is there an appropriate level of challenge for all?

- Does our progression model allow for a mastery approach where the higher-performing learners are sufficiently stretched and lower-performing learners are effectively supported, and yet the integrity of our teaching sequence is still maintained so that no learner runs too far ahead or falls too far behind?

- Do we bake retrieval practice into our curriculum to ensure we activate prior knowledge as and when appropriate and keep that prior knowledge accessible to learners so that they can make connections between what they learned yesterday, what they’re learning today, and what they will learn tomorrow? Does this enable learners to forge ever-more complex schemata in long-term memory and aide automaticity?

Does our curriculum help to tackle social justice issues?

- Have we planned to teach the knowledge and cultural capital our learners need to access and understand our curriculum and go on to thrive in later life?

- Are there high academic ambitions for all learners, and do we offer disadvantaged learners and those with SEND the same curriculum experience as their peers rather than ‘dumb down’ or reduce the offer?

- Do we identify the barriers some learners face in school and within each subject discipline, including though not solely a potential vocabulary deficit, and do we plan effective support strategies to help overcome those barriers?

- Whenever we use additional intervention and support strategies to help disadvantaged learners and those with SEND, do we monitor their effectiveness as they’re happening rather than wait to evaluate their eventual success once they’ve ended?

…The above is by no means an exhaustive list but at its heart is a simple self-evaluative question: Is your curriculum working for all your learners?

Implementation

As well as evaluating the effectiveness of your curriculum planning – or intent – you should also evaluate how well the curriculum is translated into practice in the classroom – in other words, its implementation. To help, ask:

Do teachers have expert knowledge of the subjects they teach?

- If not, are they being supported to address gaps in their knowledge so that learners are not disadvantaged by ineffective teaching?

- Does the school support an effective programme of subject-specific professional development as well as training on generic pedagogy?

- Do the teachers assigned to each cohort, each year group and each level and type of qualification have the knowledge and experience to teach it well? Thus: is timetabling as effectiveness as it could be?

Do teachers enable learners to understand key concepts, presenting information clearly?

- Are teacher explanations effective – for example, do they make use of dual coding?

- Do teachers also model thinking aloud for learners to make the invisible visible and the implicit explicit?

- Do teachers explicitly teach the language – including tier 2 and 3 vocabulary – that learners need in order to understand the curriculum?

- Do teachers articulate clear learning outcomes and make explicit what learners should know and be able to do at the end of each sequence of lessons?

- Do teachers establish routines for classroom discussions so that all learners contribute fairly and in order that debate deepens learners’ understanding?

- Do teachers make use of ‘live’ low-stakes assessment practices such as hinge questions and exit tickets to assess learners’ understanding and to identify the gaps in their knowledge and skills, as well as their misunderstandings?

- Do they use these assessments to inform their planning and teaching so that lesson planning is fluid and responsive, rather than something to stick to religiously?

Do teachers ensure that learners embed key concepts in their long-term memory and apply them fluently?

- Is the subject curriculum taught in such a way that helps learners to transfer key knowledge to long-term memory?

- Do teachers gain the active attention of learners’ working memories and make them think hard but efficiently about curriculum content? Once encoded into long-term memory, do teachers provide plenty of opportunities for retrieval practice to ensure the knowledge in long-term memory is brought back into the working memory so that it remains accessible, and so as to encourage learners to apply that knowledge in different contexts? Is prior learning linked to new learning, so that what is taught today builds upon what was taught yesterday and so forth?

- Are explicit links made between different parts of the curriculum and indeed across curriculum areas to help make knowledge transferable and useable?

- Is teaching sequenced in practice not just in lesson plans so that learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to complete each task before they are asked to complete it, and so that new knowledge and skills logically build on what has been taught before enabling learners to make progress towards clearly defined end points?

Do teachers use formative assessment to check learners’ understanding to inform their planning and their teaching, and to help learners embed and use knowledge fluently and develop their understanding?

- Do all these assessments have a clear purpose? Do they provide valid data on which the teacher can and does act?

- Is the feedback garnered from assessments meaningful and motivating to learners? Does it help them to close the gap between their current performance and their desired performance?

- Is time set aside every time feedback is given to learners so that they can process it, question it if needed, and act upon it in class whilst the teacher is present to provide support, challenge and encouragement?

In evaluating the effectiveness of the way in which the curriculum is taught, you would do well to consider the question, ‘What is learning?’ If you define the complex process of learning as an alteration in long-term memory, then you might conclude that if nothing has altered in long-term memory, nothing has been learned. Accordingly, and in addition to the above, I would suggest you ask: How do I assess the extent to which learners transfer key concepts into long-term memory and can apply them fluently and what do I do with the findings?

Impact

As well as evaluating the effectiveness of your curriculum planning and teaching, you should measure eventual outcomes so that you can determine what learners have achieved and also the extent to which your curriculum planning and the way in which you have translated those curriculum plans into classroom practice have enabled learners to achieve what you intended for them and that you have not perpetuated or opened any attainment gaps.

Remember: the purpose of education is not just certification but to genuinely prepare learners for the next stage of their education, employment, and lives. So, what does this look like? What might you assess to make a judgment about the impact of your curriculum on learner outcomes? To help, ask:

How do we prepare learners for the next stage of their lives?

- Where do our learners go next? Does this represent a positive step in the right direction for them? Is it ambitious and challenging?

- How effective is our provision of character education? RSE? PSHE? The fundamental British values? Does this prepare learners for their next steps beyond subject qualifications?

- Do we run an ambitious programme of extra-curricular and enrichment activities which take learners beyond the academic curriculum and the taught timetable? Do we develop oracy skills, perhaps through a debating society?

What does our hidden curriculum look like and is it consistent with the taught curriculum?

- What messages does our hidden curriculum send to learners? What do the words and actions of all the adults in school say to learners about what values and attitudes matter most in life, and about how to behave as citizens and employees?

How do we develop learners’ skills?

- Are the skills that learners need in order to be prepared for their next steps explicitly planned and taught?

- Are skills developed as ‘transferable’ or through subject disciplines in domain-specific ways? NB You may decide that some skills are transferable because they are used in many subjects across the curriculum and in similar ways. Take, for example, structuring an argument, working in a team, giving feedback to a peer, internet research, note-taking, and so on.

Is the information, advice and guidance we provide impartial and effective?

- Do you offer effective impartial careers guidance and advice on further qualifications to study?

- Do learners know their options for the next stage of their education, employment and lives? Are they able to make informed decisions?

- Does future planning, including thinking about career options, help foster intrinsic motivation and lend purpose to learners’ current studies?

Do we help learners to make smooth transitions?

- Do you help learners adjust to all the changes they face whilst in education? This includes the transition between schools as well as between the various phases, stages, and years of education.