This is an edited extract from the book, School and College Curriculum Design 3: Impact. For more information on this book and the first two in the series, as well as to access a raft of free curriculum resources, visit our Curriculum Central page.

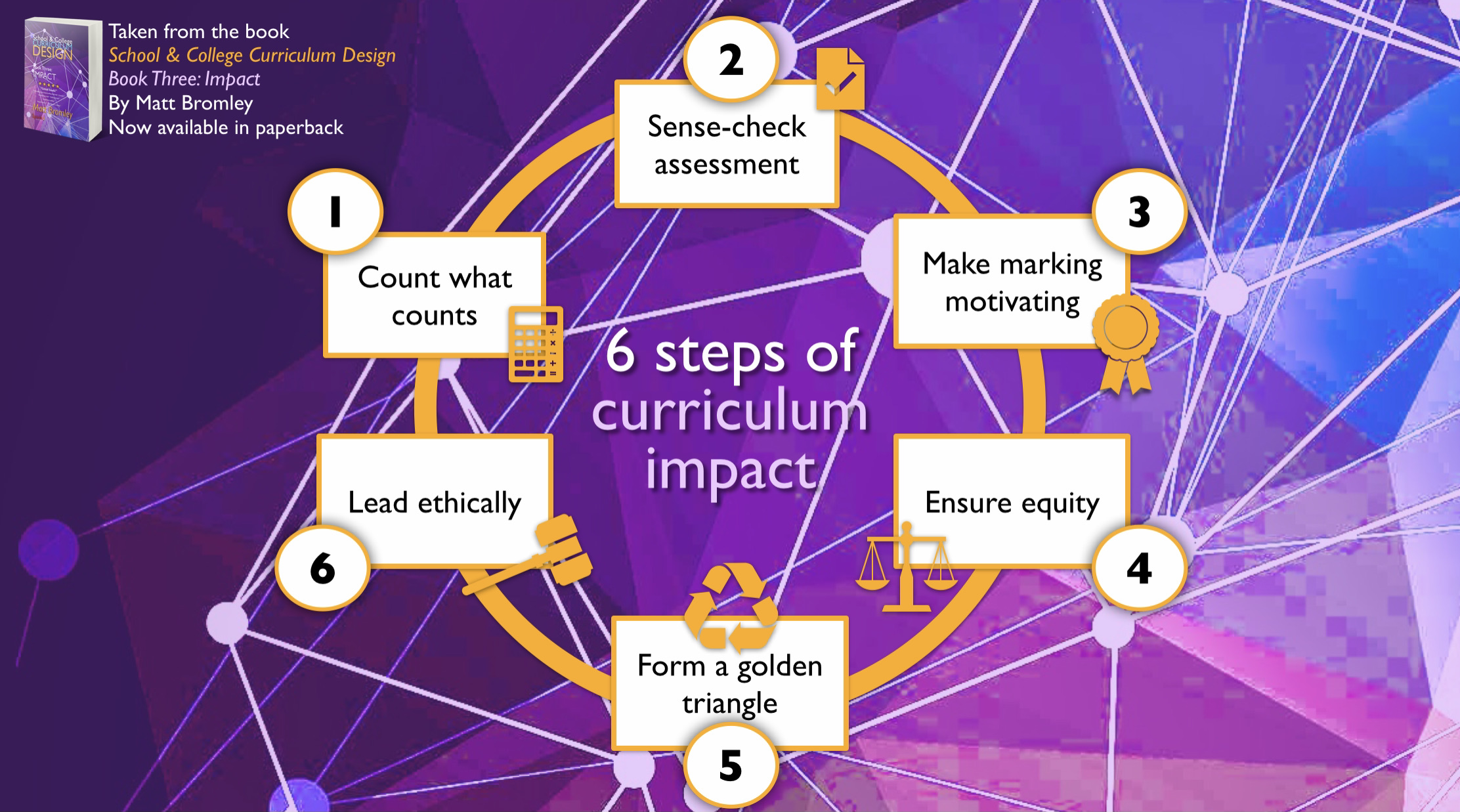

I advocate forming a ‘golden triangle’ which connects the following aspects of school management:

1. Quality assurance

2. Performance management

3. Professional development

Apex 1: Quality assurance

When it comes to quality assurance – or, as I prefer, quality improvement– I believe that we should measure the quality of education (note: not the quality of teachers or teaching necessarily) in a holistic rather than an isolated way.

An effective quality assurance process might, therefore, consist of three stages:

1. A professional conversation about subject purpose and intentions

2. A range of quality assurance activities (on which more below)

3. An action planning meeting to agree next steps

And the second stage should take myriad forms which, when triangulated, paint a holistic picture of performance. I’d suggest at least these four cornerstones:

1. Lesson observations

2. Work scrutiny

3. Review of planning

4. Review of resources

Apex 2: Performance management

When it comes to performance management – or, as I prefer, performance development – my philosophy is simple: it is no one’s vocation to fail. In other words, no one wakes up in the morning determined to do the worst job they possibly can; no one opens their eyes, stretches and yawns, looks themselves up and down in the mirror and vows to fail as many pupils as they can before nightfall. But, despite the best of intentions, sometimes some people don’t perform as well as they can or as well as we’d like.

When teachers under-perform, they need to be given time and support – including appropriate training – in order to improve.

For a long time and in too many cases, teacher performance management in schools and colleges was synonymous with an annual lesson observation. The lesson judgment – which usually took the form of a single number from 1 to 4, modelled on the Ofsted rating system – determined whether or not a teacher passed the appraisal cycle successfully and thus could escape the sanctions of ‘capability’ and – where relevant – be rewarded with pay progression.

Thankfully, this is much less common today than it once was, say, five or ten years ago. But it is not unheard of and even if graded lesson observations have ended, for too many teachers, appraisal cycles are still won or lost in a lesson observation. This is problematic because lessons observations alone – no matter how professionally and pragmatically they are carried out – do not enable us to accurately judge a teacher’s effectiveness in the classroom, let alone their entire professional contribution.

The main thrust of my argument with regards performance management is simple: we should move away from performance management and towards performance development. In other words, we should avoid instigating a pass/fail system of appraisal that assumes teachers are either good or bad. Instead, we should strive for a system that recognises the complexity of the job, accepts that people have good and bad days, that many more factors affect pupils’ progress and outcomes than an individual teacher, and that the goal is to help everyone – no matter their career stage – improve over time (whilst acknowledging that everyone is human, and no one is perfect).

Let me emphasise those key points again…

Performance management should:

• Recognise the fact that teaching and learning are highly complex and cannot be reduced to a checklist or rubric

• Accept that a teacher’s performance isn’t uniform – they have good and bad days, and an ineffective lesson does not mean they have failed

• Acknowledge that pupil outcomes are affected by many factors beyond a teacher’s control

• Aim to help every teacher in a school to improve, no matter their career stage or training needs

• Promote collaboration rather than competition, and incentivise team-working and joint practice development

So, put simply, it is my belief that performance management – if it is to ‘measure’ anything – should measure a teacher’s willingness to engage in professional development activity and improve over time. As a natural progression from this, it is reasonable to assert that an appraisal system could consist quite simply of one professional development target per year and be reviewed at the end of the cycle on the extent to which a teacher has engaged in CPD activity, tried new approaches and evaluated their impact. Talking of which…

Apex 3: Professional development

Professional development works best, I find, when it is worthwhile, sustained and evaluated.

Firstly, CPD should provide opportunities for external expertise to be injected into a school and so take the form of INSET events led by a guest speaker. This is important because schools must not become isolated from the outside world. If they do, they are in danger of becoming ‘sausage factories’ which keep churning out the same results precisely because they keep putting in the same ingredients.

External speakers, trainers and advisors can help schools to challenge the status quo, to question hitherto unquestionable practices, and to sense-check their work against other schools. They can also provide a new way of thinking about ideas and approaches.

Secondly, I think CPD should also be external in the sense of teachers accessing conferences, training courses and networking events outside the school gates. Such events provide an opportunity for teachers to stop, think and reflect on their current practices and to talk to colleagues from other settings and thus share ideas.

Thirdly, I think CPD should take myriad forms and not be limited to formal training courses. CPD can include engaging with academic research, networking online, and trying out new strategies in the classroom then evaluating their impact. In the case of vocational teachers in FE settings, CPD can – and indeed should – take the form of workplace visits to ensure their industry knowledge is kept up-to-date and relevant.

Fourthly, I think CPD should be teacher-led and thus afford teachers the opportunity to share best practice with colleagues from their own departments and schools and seek help and advice from colleagues who teach in the same setting. Peer-observations and peer-teaching are particularly helpful here. A note of caution, though: It is important that there is a structure and a clear focus for any teacher-led CPD in order to avoid it becoming simply a ‘talking shop’.

And finally, CPD should perform the twin functions of innovation and mastery. In other words, professional development should not just be about learning new ways of working – professional development for innovation – although this is undoubtedly important. Rather, it should also be about helping teachers to get better at something they already do – professional development for mastery. Professional development for mastery is about recognising what already works well and what should therefore be embedded, consolidated, built upon, and shared.

Now visit our Curriculum Central page for more curriculum resources including a preview of Book Three.